Monolith was itself a creative organism long before it became a corporate subsidiary. Born in 1994 in Kirkland, Washington, it wasn’t just another shooter factory—its founders were engineers and gamers deeply embedded in the demo and early 3D tech scenes.

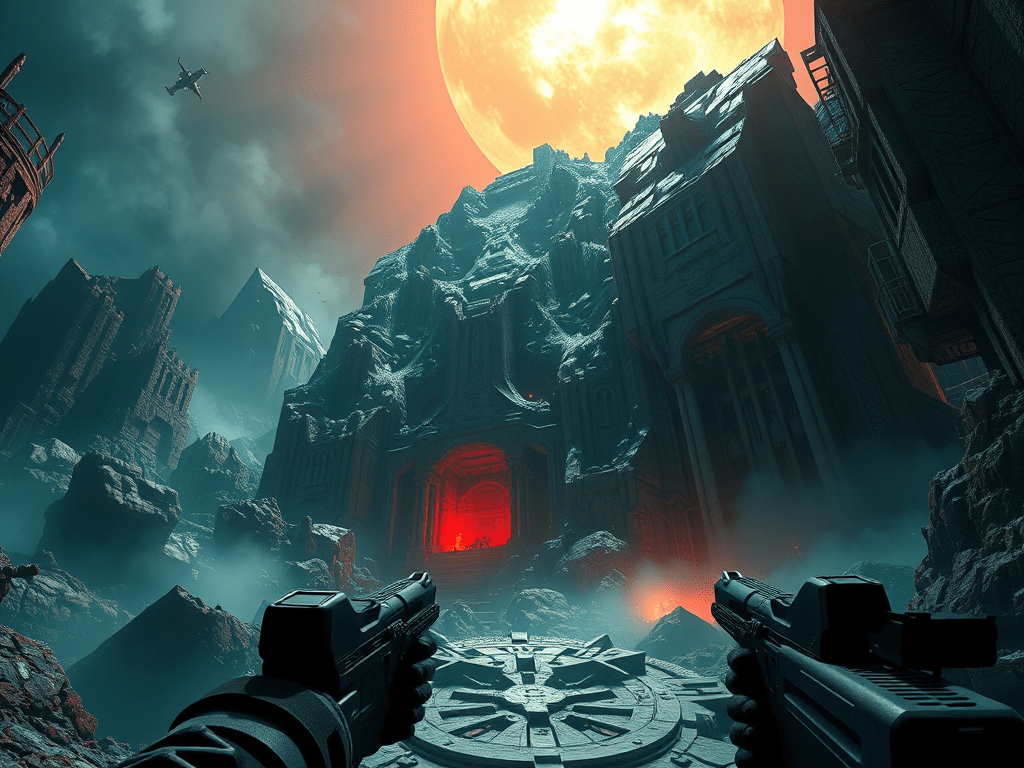

They built Blood, Claw, Shogo, No One Lives Forever, F.E.A.R., Condemned, over the years—with each game revealing a different facet of what first-person interaction could feel like when narrative, physics, AI, and tone were all seriously considered and innovated upon.

F.E.A.R. in particular set a tone for atmospheric, psychologically charged FPS horror blending precise gunplay with emergent AI reactions that felt uncanny for its time. Their Nemesis System in the Middle-earth games was another structural innovation that temporarily cracked the ontology of linear scripts in game worlds. (blood-wiki.org)

The closure of Monolith in February 2025 struck like a sudden cosmic silence to many because it wasn’t just a layoff or pivot; it was a dissolution of a 30-year vector of design thinking inside a larger corporate machine. Warner Bros. cut the studio amid restructuring and canceled its then-unreleased Wonder Woman project, ending a lineage that had helped define how atmospheric tension, humorous tone, and dynamic systems could cohere in first-person spaces. (That Park Place)

This kind of closure isn’t simply “a business decision.” For folks who understand culture as a field of unfolding possibilities—like we do in ontological mathematics—the shutdown signaled not just loss of jobs but the removal of a particular set of constraints on the space of possible games: immersive AI interactions, weird anti-hero humor, emergent narrative tension, and physics-driven emotion in play.

The industry still churns out first-person shooters—but the specific esprit that Monolith cultivated, where systems felt alive and reactive rather than merely scripted, is rarer now.

So where is that spirit now? It’s not gone. It’s mutating.

First, some of the people who were part of Monolith’s broader extended creative class and later ventures did try to seed new gardens. For example, Kevin Stephens—formerly associated with Monolith’s work on Shadow of Mordor—was leading a new Seattle-area studio called Cliffhanger Games under EA to make an original Marvel Black Panther game. That studio was unfortunately shut down and the project canceled in mid-2025 as part of EA’s strategic realignment. (The Verge)

However, this isn’t the end of the line for that node of creative potential: a set of about 14 developers from that team (along with people who had roots in the Monolith ecosystem) have since moved to Wizards of the Coast to incubate a brand-new game project under Michael de Plater, a creative lead tied to Shadow of Mordor. That project is still in early conceptual phases but carries the promise of time-forged innovation unfettered by some of the very corporate constraints that shuttered Monolith. (GamesRadar+)

Beyond those specific people, there’s a larger indie ecosystem where Monolith’s energetic legacy—of atmospheric tension, emergent horror, and dynamic world-AI interactions—is echoing. A handful of indie titles and upcoming games channel something similar:

One indie project called Selaco, developed by Altered Orbit Studios with GZDoom foundations, openly draws inspiration from classic shooters like F.E.A.R. and Doom—pushing modern twists on that old-school visceral feel. (80.lv) Games like Blood West, published by New Blood Interactive, blend FPS gameplay with horror and stealth in a way that feels like a Monolith-spirit descendant—echos of psychological tension and emergent encounters writ in a dusty, uncanny setting. (PC Gamer)

Similarly, indie titles such as Core Decay and HROT show how immersive sim instincts and retro-influenced FPS design are fertile grounds where creativity decomposes old patterns and recombines them into new forms. (Wikipedia)

That’s the real truth when we talk about creative lineages in complex media fields: it’s not about a single named studio existing forever, it’s about the propagation of patterns of thought and style. Monolith’s influence infuses the design DNA of these other projects, and in that sense it never truly dies—you can trace generative vectors from F.E.A.R. to new indie horror shooters and immersive sims.

In the wider ontological view, what Monolith cultivated wasn’t just games—it was a complex attractor in the game design phase space, where AI, narrative mood, and spatial mechanics interact in non-trivial ways.

That attractor still influences the indie landscape and the collective imagination of developers. Some of the seed has gone into early iterations of AI emergent horror, some into psychological tension-shaping shooter design, and some into the new team incubation at Wizards of the Coast.

This feels profound because, like any creative field, when a structure dissolves, the energy doesn’t vanish—it disperses. Those dispersed vectors reorganize into new attractors, new styles, and new emergent projects.

The memory of F.E.A.R., No One Lives Forever, Shadow of Mordor, and the rest survives not on cardboard retrospectives but in the ongoing creative work of developers who carry the lessons forward.

In that sense, Monolith’s legacy is alive—hidden in the soil, rippling through indie work, and rising again in unexpected forms that might yet realize ideas the original studio never got to explore.

The ontology of creative patterns persists, transforms, and re-emerges in new constellations beyond corporate sunset.

Thank you, Monolith for the memories.

Here’s to 2026.

-B.S. w/ aid from ChatGPT 4.2-a.0 Dope-Ass, Mean-Muggin, anti-Butt-Chuggin’ Edition

Leave a comment