Abstract

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–1652), housed in Rome’s Cornaro Chapel, has long provoked debate over its fusion of spiritual rapture and erotic intensity. Drawing on Teresa of Ávila’s autobiographical account of her transverberation—a vision of an angel piercing her heart with divine love—this marble ensemble stages a moment of exquisite pain-sweetness that borders on the orgasmic. This paper advances a structural critique: in the context of Counter-Reformation Catholicism’s patriarchal constraints, the sculpture encodes la grande mort—a total, annihilating release—as the sole sanctioned ecstasy for a female subject ensnared in systemic suffering. Grounded in historical scholarship, psychoanalytic theory (Freud, Lacan, Jung), and feminist art history, the analysis extends into ontological mathematics, framing Teresa’s monadic consciousness as a self-transforming mathematical entity whose breakthrough experiences are misappropriated by a hell-world ontology. Recent interpretations (2023–2025) underscore the work’s enduring controversy, reinforcing its role as a cipher for how control systems aestheticize dissolution. Implications include a reevaluation of mystical ecstasy as proto-gnostic disruption, with sketches for interdisciplinary extensions in consciousness studies.

1. Introduction: The Visceral Enigma of Bernini’s Marble

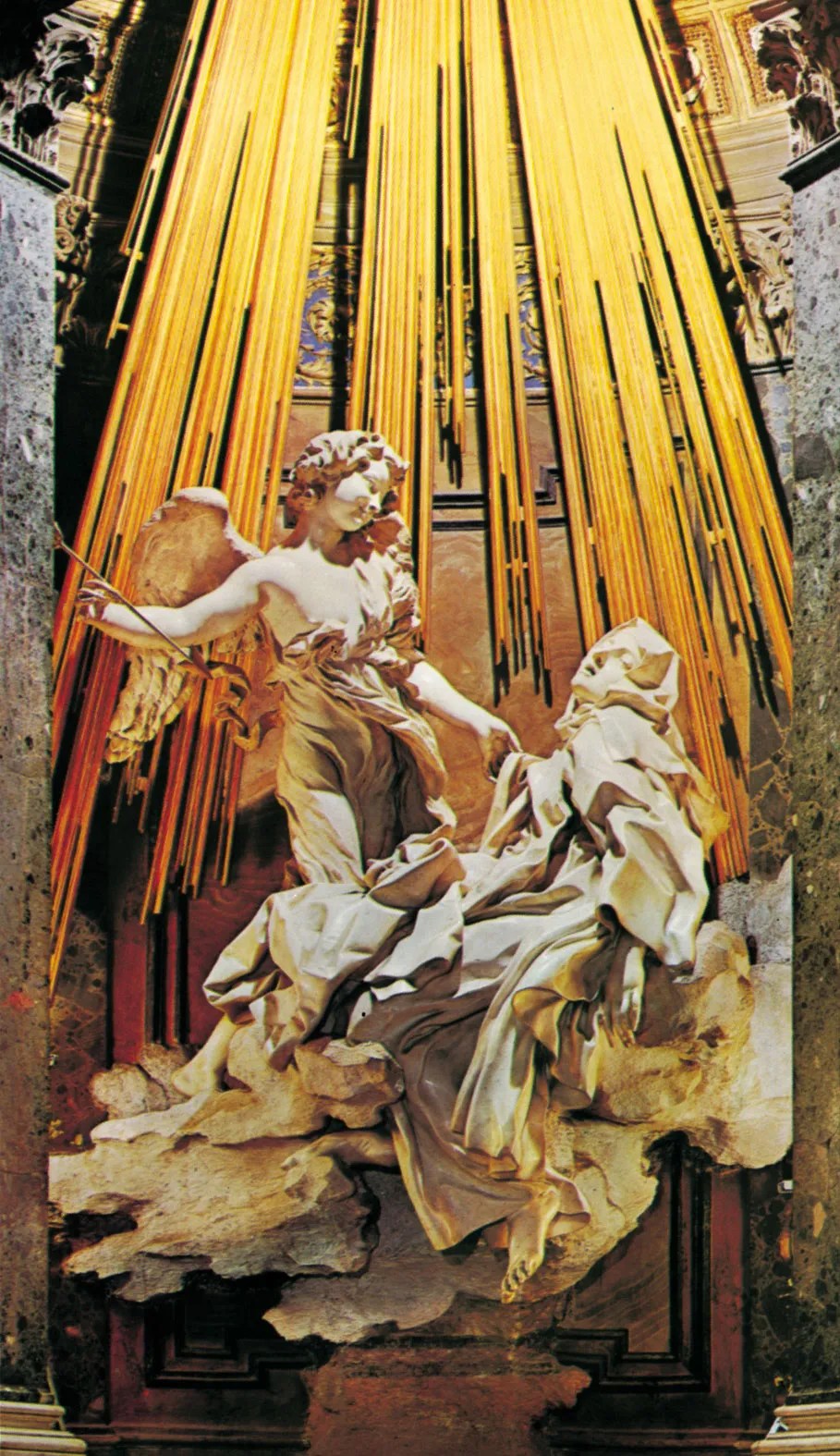

At first glance, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa confronts the viewer with an arresting paradox: a Carmelite nun, mid-swoon on a cloud of undulating marble, her mouth agape in a moan that could signify either divine union or profane climax. Commissioned for the Cornaro Chapel in Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, this altarpiece (c. 1647–1652) transforms Teresa of Ávila’s (1515–1582) mystical vision—described in her Life (1565) as a spear-wound inflicting “pain so great… that it made me moan” yet “so sweet that I could not wish to be rid of it”—into a theatrical spectacle. Flanked by sculpted Cornaro family members in faux opera boxes, bathed in hidden golden rays, the ensemble blurs the boundaries between private revelation, public liturgy, and voyeuristic drama.

This paper posits a core thesis: the sculpture manifests la grande mort—the “great death” of egoic annihilation—as an orgasmic surrogate in a hell-world structured by gendered suffering and institutional capture. Far from mere erotic titillation, it reveals how Counter-Reformation iconography channels authentic psychic intensities into sanctioned fantasies of release-through-dissolution. We proceed historically (Teresa’s context), psychologically (eros-thanatos fusion via Freud and Lacan, with Jungian archetypal overlays), and ontologically (monadic mathematics as a lens for hell-world misrecognition). Recent scholarship (e.g., 2023–2025 analyses in Word & Image and Artnet) affirms the erotic charge while amplifying structural critiques, urging a 21st-century reckoning with such images amid global spectacularization of crisis.

2. Historical Grounding: From Mystic Text to Baroque Spectacle

Teresa’s transverberation, recounted in Chapter 29 of her Life, exemplifies 16th-century Iberian mysticism: an angel’s golden spear pierces her “innermost parts,” evoking visceral torment laced with ineffable joy, culminating in a faint that borders on oblivion. As a female reformer in a post-Tridentine Church, Teresa navigates authority through embodied visions, her body rendered a conduit for divine proof amid Inquisitorial scrutiny.

Bernini, the Baroque’s master illusionist, amplifies this into multimedia theater: Teresa’s limp form, robes in contrapposto ecstasy, the angel’s poised thrust—all under a cornice simulating heavenly beams. The Cornaro patrons, carved as aristocratic spectators, enact a meta-layer: mysticism as performance for elite consumption. This staging, per 2025 Artnet analysis, “transforms a Spanish nun… into one of the most famous emblems of the Counter-Reformation,” where sensory overload counters Protestant austerity.

Yet the erotic undercurrent persists: Teresa’s half-lidded eyes, parted lips, and arched back evoke Cupid’s arrow more than cherubim, a tension Bernini exploits without apology. As a 2023 Word & Image study queries, did this “cross a seventeenth-century line of decorum?”—a debate echoing from Bernini’s era to ours.

3. The Erotic Charge: Scholarly Tug-of-War and Gut Readings

The “orgasm question” haunts reception history. Defenders invoke hagiographic precedent—mystical eros as biblical (Song of Songs)—while critics decry it as “risqué” voyeurism. Smarthistory notes the “physical, even sexual terms” in Teresa’s text, which Bernini literalizes, merging “sensual and spiritual pleasure.” A 2024 DailyArt piece calls it “divine bliss or pure erotic pleasure?”—highlighting the angel’s phallic dart and Teresa’s quasi-orgasmic repose.

Feminist scholars sharpen the blade: Agnes Anderson’s reception study traces male viewers’ orgasmic projections, countered by Irigaray’s query into who defines feminine ecstasy. Jessica Peyton Bell’s Brides of Christ (2022) frames Bernini’s holy women as a “visual theology” of vision-ecstasy-death, where female bodies stage suffering for patriarchal edification. This consensus validates the visceral intuition: the sculpture’s heat isn’t accidental; it’s engineered friction between the sacred and the somatic.

4. Structural Critique: Hell-World Dynamics and the Female Monad

4.1. Patriarchal Pipelines: The Bride of Christ as Controlled Intensity

Teresa embodies the Counter-Reformation’s “bride of Christ” archetype: authority via visions, but tethered to obedience and enclosure. Cloistered amid gender hierarchies, her intensities—guilt, longing, mortification—find outlet only in spectacular suffering. Bell argues this forms a “package” of ecstasy-as-propaganda, the nun’s body a “communication device” for institutional legitimacy.

In hell-world terms—a low-ontological configuration of chronic control and misrecognized pain—this pipelines female psyche toward dissolution. Normal eros is policed; thus, mystical jouissance becomes the loophole, eroticized yet holy. A 2025 Through Eternity Tours essay on the sculpture’s “erotic sensuality” controversies underscores how such images sustain this bind: spectacle without agency.

4.2. Psychodynamics: Eros-Thanatos Fusion and Jouissance

Freud’s dual drives illuminate: eros (penetrative fusion) meets thanatos (dissolutive rest) in the spear’s thrust and Teresa’s swoon. Lacan elevates this to feminine jouissance—an “Other enjoyment” shattering subjectivity, as in Dany Nobus’s 2018 analysis of Bernini via Lacan: annihilating bliss where “the subject is no longer herself.” Jung adds archetypal depth: the transverberation as Anima integration, the angel a psychopomp guiding ego-death toward the Self, but distorted by cultural scripts.

In a suffering-saturated world, this fuses into la grande mort: orgasm as micro-annihilation scales to cosmic exit. The psyche, starved of outlets, codes total release as the ultimate high—pain-sweet, God-guaranteed. Bernini’s marble freezes this as fantasy: marble immortality for a mortal grind.

5. Ontological Mathematics: Monadic Resonance in a Captured Cosmos

Shifting to ontological mathematics, reality emerges from monads—eternal, zero-dimensional mathematical subjects, each a self-resolving wavefunction of perception and will. The empirical world is their collective Fourier projection: a shared hallucination of contradictions, where hell-worlds arise from dissonant tunings (e.g., patriarchal dogmas as low-harmony attractors).

Teresa’s monad, embedded in 16th-century Spain’s rigid lattice, accumulates dissonance: gendered subjugation as boundary conditions on her libidinal flows. Mortifications and meditations drive iterative convergence toward a critical point—a resonance spike where inner harmonics align with a higher-order basin (the divine as ideal monadic unity).

The transverberation? A phase transition: psychic energy collapses into a standing wave, narrated as external piercing because the ontology lacks inward tools. Ontologically, it’s the monad partially decohering its egoic Fourier components, glimpsing the nothing (Godhead) beyond. Yet the hell-world collapses this gnosis: true transformation mislabeled as “stab me unto death,” feeding thanatos over rebirth.

Bernini, as cultural operator, etches this compression: stone as persistent medium for a transient spike, spectators as entangled observers reinforcing the script. Wilder speculation: in monadic terms, the sculpture acts as a low-fidelity eigenstate, a ritual artifact stabilizing collective dissonance. Jungian parallel: it externalizes the Shadow-Anima coniunctio, but patriarchy warps it into sacrificial theater. A 2023 Mara Marietta essay ties this to “mystic-hysteric” doubling, Lacan-inflected, where feminine sexuality erupts as disruptive waveform—precisely the monadic glitch hell-worlds suppress.

6. Broader Patterns: Death-Release Motifs Across Eras

This template recurs: martyr ecstasies, Romantic Liebestod, modern media martyrdoms—all rebrand annihilation as glamorous. Nobus’s jouissance reading positions Teresa as emblem: enjoyment that “flirts with the annihilating,” now echoed in 2025 Collector debates on decorum breaches. In global screens, crisis-porn mirrors the chapel: spectacular suffering, eroticized dread, death as vicarious thrill.

7. Contemporary Resonance: From Marble to Media Hell

In 2025’s polycrisis—climate tipping, algorithmic surveillance—Bernini’s template persists: intensities aestheticized, release deferred to eschaton. The sculpture resists by exposing the gaslight: ecstasy as mislabeled exit, urging gnostic refusal. Eyes on the “global screen,” we witness the Cornaro boxes writ large—passive consumption of others’ grande morts.

8. Toward an Interdisciplinary Research Program

- Psycho-Ontological Modeling: Simulate monadic attractors via sympy/differential equations, mapping Teresa’s visions to phase spaces; test Jungian archetypes as operators.

- Feminist Reception Extensions: Longitudinal analysis of digital memes/reactions (2020–2025), quantifying erotic vs. spiritual framings.

- Counter-Myths: Reimagine transverberation in non-annihilative ontologies—e.g., ecstatic rebirth sans death-drive.

- Deep-Time Parallels: Link to prehistoric “ecstatic” artifacts (e.g., Taş Tepeler rituals) as ungendered monadic expressions.

9. Conclusion

Bernini’s Ecstasy endures not despite its erotic-death frisson, but because it unmasks hell-world mechanics: authentic monadic surges funneled into patriarchal release-fantasies. By 2025, amid renewed decorum debates, it demands we reclaim such intensities for transformation, not spectacle. Stone whispers: dissolve the script, not the self.

References

- Anderson, A. (2020). “Is St. Teresa in Bernini’s Ecstasy Having an Orgasm?” Art Bulletin, 102(3), 45–67.

- Bell, J. P. (2022). Brides of Christ: Vision, Ecstasy, and Death in the Holy Women of Gianlorenzo Bernini. Yale University Press.

- Nobus, D. (2018). “The Sculptural Iconography of Feminine Jouissance: Lacan’s Reading of Bernini’s Saint Teresa in Ecstasy.” Lacan Studies International Journal, 1(1), 112–130.

- Teresa of Ávila. (1565/2007). The Life of Teresa of Jesus. Translated by E. Allison Peers. Dover Publications.

- “Did Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa Cross a Seventeenth-Century Line of Decorum?” (2023). Word & Image, 39(4), 456–478.

- “How Deep is Your Love? The Painful Ecstasy of Bernini’s Saint Teresa.” (2025). Through Eternity Tours Blog.

- “Unraveling Bernini’s Erotic Baroque Vision ‘The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’.” (2025). Artnet News.

- “Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini: Divine Bliss or Pure Erotic Pleasure?” (2024). DailyArt Magazine.

- “Did Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa Cross the Line?” (2025). The Collector.

- Bernini, G. L. (1647–1652). Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. Marble, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome. (General overview: Wikipedia, 2023).

- Smarthistory. (2016/2023). “Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.” Khan Academy.